We are thrilled to announce that the Judges' Winner for the LoveReading Very Short Story Award is: Oh, I Do Love A Banana by Susanna Crossman.

It was really important to us at LoveReading to have the two separate awards as we felt, as a book loving community, that we wanted to include our members in the award process. The fact that the judges chose a separate winner to our members proves how diverse and inclusive the book loving community can be. Both of the winning entries, while very different in content, are truly beautiful and reach out to our emotions.

We asked both of our winners some questions, and I loved finding out more about them and how their stories came into being… we have also included their winning stories.

Huge congratulations, we are absolutely thrilled with our two winners for the first ever LoveReading Very Short Story Award, can you tell us a little about yourself?

I was born in Britain but am now based in France where I live with my partner and our three daughters. I write fiction and non-fiction, in both English and French, and have recent work in ZenoPress, The Creative Review, 3:AM Journal, The Arsonista, Litro and elsewhere. My essay, The Nomenclature of a Toddler, inspired by my youngest daughter’s use of language, was nominated for Best of The Net (2018). As a writer, I also regularly collaborate in arts projects, currently the English-Spanish prose film, 360° of Morning – three artists in three mornings in three different countries. When I am not writing, I work internationally as a clinical arts therapist and lecturer, specialising in mental health, creativity and non-verbal communication.

Who was the first person you told when you heard you’d won and how did you feel?

When I received the email telling me I had won the prize, I was in the middle of a crowded waiting room on a Friday evening at the Gare du Nord in Paris. Having texted my partner, I was still so excited that as soon as I got on my train I had to share my news with the lovely Franco-Moroccan woman who was sat next to me. We ended up chatting the whole journey to London about books, cooking and destiny.

Have you always loved the written word, when did you first start to write?

Both reading and writing are a daily constant in my life. I taught myself to read before I went to school, and as a little girl, I would visit my local library every Saturday, rush home and devour my four books. I began writing stories when I was seven and won short story competitions when I was teenager. Having studied Drama, I then wrote for theatre and academically. About five years ago, I started writing more seriously, and was lucky enough to have my work spotted by great agent Jessica Craig.

Who are your booky inspirations?

I read very broadly and love literary fiction, non-fiction, crime, children’s fiction and more. Currently, I am re-reading all of Virginia Woolf’s work, have just started The Island of Second Sight by Albery Vigoleis Thelen, and Emily Wilson’s new translation of The Odyssey. I am regularly inspired by writers like: Marguerite Yourcenar, Iris Murdoch, Leonora Carrington, David Grossman, Olivia Manning, Milan Kundera, Helen Dunmore, Assia Djebar... I have also just discovered Ann Quin, a fascinating, experimental British writer.

How and where do you like to write?

I am answering these questions from my local library. I love reading and writing in libraries and even visit libraries when I travel. I agree with Alberto Manguel that libraries “ have always seemed to me pleasantly mad places, and for as long as I can remember I've been seduced by their labyrinthine logic,.”

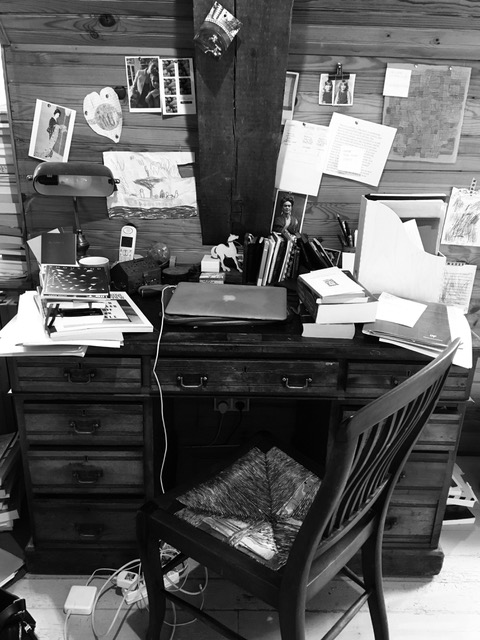

At home, I also write in the beautiful space that I have in my current house, on my grandfather’s desk.

How did your Very Short Story arrive on the page? Was it something already in your mind or did it say hello when you decided to enter?

Often my stories tell themselves and evolve as I write them. The themes of this story were definitely already on my mind. I wanted to explore the subject of aging, solitude and Stanley’s relationship to time and memory, interweave the layers of his inner and outer lives, his idea of home and safety. When I write, I like to begin from banal, ordinary actions that each of us undertakes, like supermarket shopping, and try to trace the lines to the extraordinary poetry of each human life. At home, I actually have a collection of supermarket shopping lists that I have found at the bottom of trolleys, the tiny details of human lives.

Are you excited to hear your story read by a professional actor on the podcast? Are you going to listen to it for the first time by yourself or with anyone else?

I heard a snippet of the reading when Elena Lappin interviewed me. Originally, I trained and worked as an actress, and do a lot of my own readings for literary events. So, I was thrilled to hear this reading. When I heard the actress’s beautiful voice, it felt like my story came alive. Suddenly, I could picture Stanley in the supermarket queue, gazing down at his bunch of bananas.

What is your favorite book from childhood, do you still have it and what was it about that book that you adored? I still have all my childhood books, as well as my grandparents and great-grandparents books. One of my favourites when I was young was The Little Princess by Francis Hodgson Burnett. I was drawn to the idea of a little girl being an outsider, losing everything and surviving through her imaginary world. My childhood was quite unconventional (as I grew up in a commune) so, in-between times I was also reading raw feminist novels like The Women’s Room by Marilyn French.

Can we have a peek at your favorite bookshelf or shelves please...

Which is your most beloved and well-read book?

Impossible to choose one. But, I regularly re-read Mrs Dalloway and To The Lighthouse, Memoirs of the House of the Dead by Dostoevsky, French philosopher Pierre Hadot and all of the Ian Rankin Rebus books.

What advice would you give to someone who is thinking of entering next year?

Read, read and read some more. Also, keep sending your work out, and don’t be too disappointed when it is rejected. I just had a new draft of a story accepted for publication that I first wrote ten years ago. Also, learn to edit, Annie Dillard’s This Writing Life is excellent on editing. I would recommend having a trusted reader/editor. I work very closely with another writer, and we read and edit each other’s work. Since we started this process a few years ago, I have learnt so much.

Where are you planning to go next on your writing journey?

This year promises to be very exciting and very busy. Recently, I finished a memoir exploring my grief after losing my sister, sisterly relationships and our childhood in a commune, which is being read by publishers now. This spring, I have stories coming out in the anthology We’ll Never Have Paris (Repeater Books), in Neue Rundschau, S. Fischer (my first time having a story translated into German), and in The Lonely Crowd. My prose film, 360° of Morning, is currently being screened around Europe, and I just got funded to write the dialogue for a French cartoon pilot about fish.

I am also in the midst of a new novel…

Keep up to date with Susanna Crossman:

Website: https://susanna-crossman.squarespace.com

Twitter: @crossmansusanna

Listen to Oh, I Do Love A Banana on the LoveReading Podcast by clicking here.

Oh, I Do Love A Banana

Stanley Green couldn’t remember if he needed cheese. He looked down at the supermarket conveyor belt. His shopping splayed out on old black rubber: Two bunches of bananas wrapped in cellophane. A bottle of bleach. Yellow and white. He felt his stomach lurch, patted his pockets for his list, written that morning with an inky biro. In the crowded supermarket, 80’s music was playing, Don’t You Forget About Me? Stanley drummed stained fingers on his thigh, glanced impatiently at his watch. It had stopped. He shook his wrist, tapped the glass. It must be early evening. Home soon, Stanley thought, home soon. His thought was like the first sighting of land from a ship. Desperate, warm and glorious.

In the queue, in front of Stanley, was a woman. Long hair, a tight dress holding her body in curves. On the conveyor belt, a thin plastic bar separated Stanley’s shopping from the woman’s: one carrot, an onion, minced beef, a giant bar of Dairy Milk, a glossy magazine. Stanley suddenly pictured his wife, Helen, evenings spent in the hoovered lounge, flicking through magazines, turning pages sharply with her long, wine-colored nails. Looking up, she would ask, “Pass me a banana Stanley,” and then peel the skin off, bite into creamy flesh, saying, “Oh, I do love a banana.” But Helen was dead now, terrible business.

Stanley looked back at the black conveyor belt, the scuffs and scratches made him think of night skies, the lines between stars: the constellations of The Plough, the Big Dipper. He searched for a mark to be his North Star, but a voice interrupted him, “Move mate!” Stanley turned. Behind him was a scowling boy with earphones, an over-size tracksuit, clutching a large can of deodorant, a pack of extra-strong cider, and a single rose. “Move mate,” he repeated.

Stanley moved. The boy put on his shopping on the conveyor belt. Now, Stanley was hemmed in tight, between the woman and the tracksuit boy. The only way to go was forward, shuffling in his loafers that needed to be re-heeled. The conveyor belt buzzed. Stanley hated tracksuits. Once, in his job as a tailor, he had had to make velvet tracksuits for the whole family of an Arab millionaire.

Stanley stared at his fingers. He was convinced he had had five things to buy. One item for each finger. Bananas, bleach and- When he worked, he had put a thimble on his thumb, protecting his skin against sharp tailoring tools: scissors, needles and pins. Everyday, he had used brown paper patterns to record customers' measurements, shoulders, chest, inner and outer thigh. His two hands, Helen said, “made miracles.”

In front him, the woman put her shopping in a bag. The onion and the carrot disappeared. Stanley glanced at his bananas, recalled a song from his childhood, “Bananas in Pajamas”. In the song, bananas eat teddy bears, but now that seemed impossible, for a banana to eat a bear. In the queue, Stanley almost laughed out loud. He looked at his loafers, knew he couldn’t laugh here.

At home, he often talked to himself. Wiping surfaces, he’d say, “Come on Stanley. Clean the house. Pull yourself together. Helen I miss you. Oh why?” Inside his four walls, the heating on full blast, his words babbled, a soliloquy. The house was a blanket, beige and warm. Sometimes, in the blind comfort, his litany blended with tears and he would fall to his corduroy knees. The only place he could be.

Now, he heard a loud voice, the woman took her bag, said, “Goodbye. Goodbye” Stanley saw her curves go out the door, and longed to follow her. He’d been a dancer in his day; all Helen’s friends had wanted to dance with him, be twirled and turned. But, he was never a bastard, he told himself. Never.

The conveyor belt advanced again. In the queue, the boy behind him grunted, and straightened his cans, the single rose. It was Stanley’s turn. Supermarket lights bore down on his balding head. Forcing himself forward, Stanley smiled at the cashier, “Hello”. “Warm for June’ she said. Stanley wanted to answer, “Before you look round it will be Christmas.” The words turned like circles in his mind, familiar and comforting, but somehow wrong. Instead, he said, “Yes, soon they’ll all be complaining about a drought”.

The cashier smiled. Stanley wished he had more to say, that his shopping was piled higher. He wished he had more items to buy: cheese, spray cleaner, a cauliflower, socks, a Birthday card with sparkles for his grand-daughter. Helen had written all the birthdays in a special book, she would have said, “How time flies.”

The cashier smiled at Stanley, scanned the bananas and the bleach. Three beeps. “That will be three pound fifty-seven,” she said. “Of course” Stanley reached for his wallet, but when he opened it, there was no money inside. He went to get his card, but there was nothing there. Looking up at the cashier, Stanley’s eyes grew wider and wider. They opened, ineluctably, like flowers. His heart beat. His bladder loosened. Stanley opened his mouth and closed it. He grabbed the bananas, turned and ran. “Sir!” the cashier said. “Mate” the boy shouted. But Stanley wasn’t listening, he didn’t look back, he was galloping in his loafers through the automatic doors, heading for his house.

Ten minutes, later Stanley was home. Door bolted, locked. He turned the heating up, felt a cold draft, and put an old towel by the crack under the front door. Nothing could get out, and nothing could get in, Stanley thought. In the kitchen, on the counter, was a shopping list. Without looking, whistling, he crumpled it into a ball. “Better get to the shops later”, Stanley said to himself. He ripped open the cellophane packet of bananas, peeled back the yellow skin and bit into creamy flesh. “Oh, I do love a banana,” he said.

Comments (1)

Andrea N - 27th December 2019

Sounds interesting. I was hooked from the beginning and especially when Stanley took the grocery and ran when he didn't have money.Leave A Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.