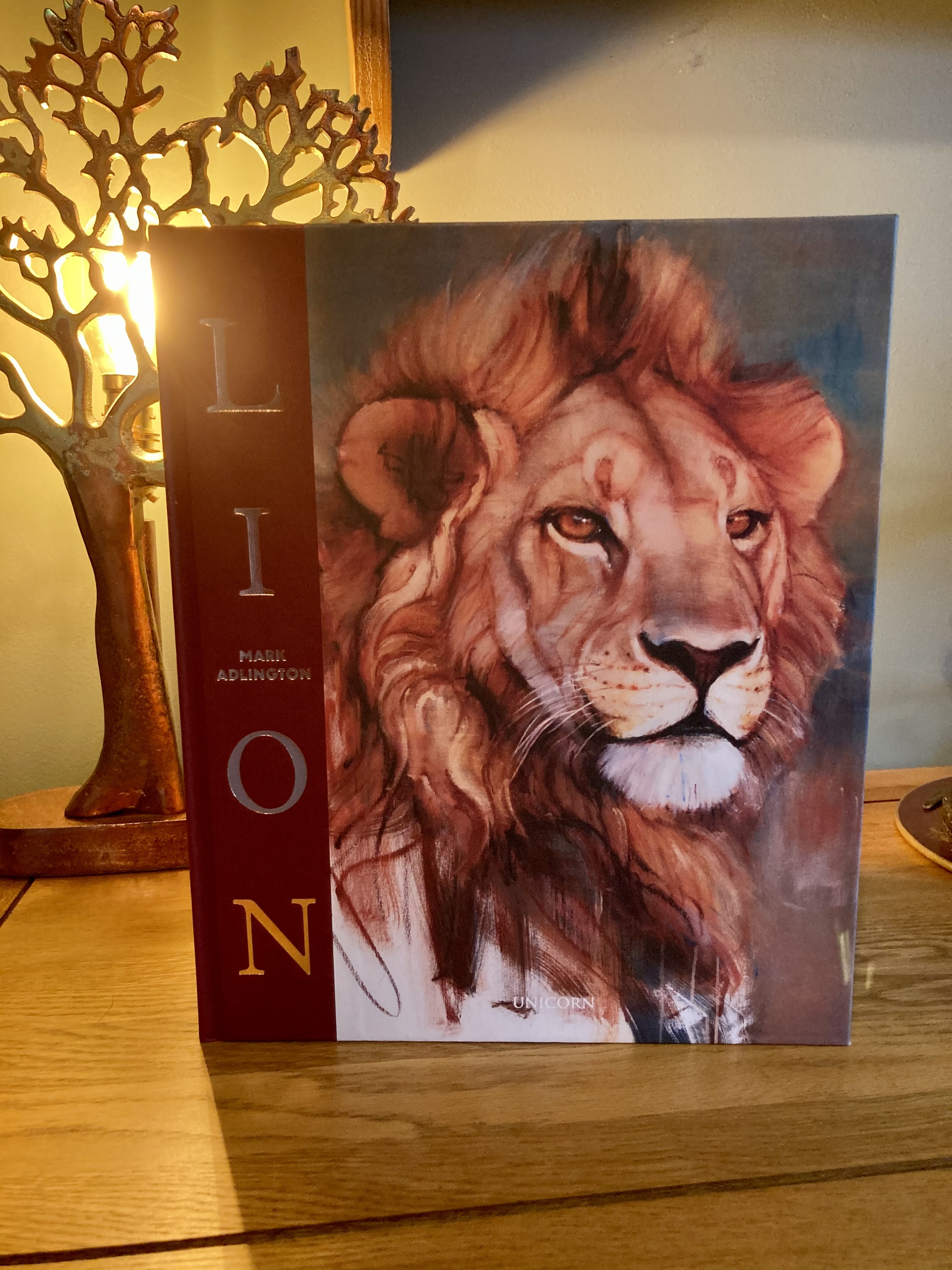

There are times when you fall completely in love with a book, and this is one of them. Mark Adlington and Unicorn Publishers have created the most stunning tribute to the lion. Lion has captured my heart, and will be a book I regularly return to. Mark is an artist (I hesitate to label him as a wildlife artist) who has championed animals on the brink of extinction. Lion introduces you to Mark’s world, and then sets you free to explore the artwork. Having felt an immediate connection to the book (yes I hugged it), I wanted to know more! Mark has shared his thoughts on the rapid decline of lions, how Lion allows the artwork to shine, and why sketches from the field have been included. Welcome Mark…

There are times when you fall completely in love with a book, and this is one of them. Mark Adlington and Unicorn Publishers have created the most stunning tribute to the lion. Lion has captured my heart, and will be a book I regularly return to. Mark is an artist (I hesitate to label him as a wildlife artist) who has championed animals on the brink of extinction. Lion introduces you to Mark’s world, and then sets you free to explore the artwork. Having felt an immediate connection to the book (yes I hugged it), I wanted to know more! Mark has shared his thoughts on the rapid decline of lions, how Lion allows the artwork to shine, and why sketches from the field have been included. Welcome Mark…

Why lions, what is it about them that so obviously calls to you?

Lions call to everyone - the lazy charismatic confidence, other worldly beauty, latent power, and that impenetrable gaze. In many ways deciding to focus on lions was the most unoriginal choice that a wildlife artist could make, but it has been a project a very long time in the making and arrived at circuitously. I spent the first twenty years of my practice both fighting the “wildlife artist” label and consciously focussing on little known obscure animals, often on the brink of extinction; the European bison, przewalski's horse, Alpine Ibex, and the Arabian leopard. I was wary of Africa and cliché, but in reality I was in denial. As a child I was obsessed with African wildlife and dreamed of working in conservation and living in the bush. Gradually the arts took over though, and when my school denied me the chance to study biology (not fitting apparently with an arts curriculum) those dreams faded. It was an art school drawing day in the British Museum and a series of relief panels made in the 6th century BC (Ashurbanipal’s lion hunts) that sparked a desire to paint lions in me that flickered away for thirty years until everything came together at the right time and this project was born in earnest. I had been strongly focussed on the arctic and the polar bear in particular - an unusual cool northern palette and a subject whose structure was hidden behind layers of fat and fur. I suddenly wanted heat and dry hot colours, line and visible anatomy. Beyond all of this I suddenly felt confident enough in my practice to think that I might have something to say about the most represented animal in the history of art, but I knew I needed to work from wild lions. An obsession was born!

Have you always been an artist, tell us more about your background in the art world, what else do you paint?

Like almost all kids I drew and painted a lot - I just never stopped. My mother is a portrait painter, and while she never really taught me, I think I was always interested in the studio and art materials and probably took a lot in by osmosis. I was keen to go to art school but was heavily discouraged by my parents, and very academic school. So in the end it was only after University and nearly three years of working for Sotheby’s Auctioneers that I had the guts to go back to art school and start again. Even as a small child it was always animals that I wanted to paint, but this was not seen as “serious” subject matter at art school, and I really had to fight my corner to continue down that path. This has been an issue since the time of Stubbs who faced similar snobbery from the art establishment, but in a sense it is exactly this misplaced sense of human beings as at the centre of the universe that needs challenging, particularly given the mess that we have made as self appointed stewards of our planet. Many of my favourite artists are abstract painters however, and have always been interested in the physicality of paint, and the images in “LION” have been made with everything from oil paint, to childrens crayons and cement colouring. So it's not immediately clear to me whether the lion is a vehicle to express paint, or the paint to express lion - I think they have to work seamlessly in tandem….

Lions, as an apex predator, have been in trouble for some time, why do you think there is so little press attention to their decline?

Yes, it's a horrifyingly rapid decline and still one that seems to attract little press attention given how obviously iconic and charismatic they are. Most people are genuinely shocked when I tell them that there are less wild lions in Africa then rhinos. They are extinct in 26 countries and occupy less than 8% of their original range. We still associate the lion with power, royalty and strength, so perhaps stories of decline and potential extinction sit uneasily with the vision of the king of the jungle that is instilled into us all from childhood. Even the latest release of Disney’s endlessly successful Lion King seemed to miss the opportunity to spread the word about the alarming reality of lion decline. Perhaps too, the reality of human wildlife conflict when it comes to lions, makes the case for conservation more nuanced. As a Londoner I struggle with pigeon infestation on my roof terrace; it's worth remembering that in asking people to live with lions, we are asking them to risk the lives of their livestock, and potentially even their families.

You’ve stayed in Kenya with the co-founder of Big Life Foundation, tell us more about that experience and how conservation supports the plight of lions.

I spent time with lions in six different places in Africa, all with differing landscapes, climates and conservation challenges. What was so exceptional about staying in the Chyulu hills near the headquarters of Big Life foundation, is that it is almost the only place in Africa where wild lion numbers have actually increased in the last twenty years. Quite apart from the indescribable beauty and space, there was something utterly unique in staying in a landscape that still supports Masai livestock herders AND wildlife outside the confines of a national park. This apparently idyllic coexistence though, is a constant balancing act supported by cleverly thought through and ongoing conservation initiatives. If the Masai were not properly compensated for lion attacks on their cattle, and didn’t benefit from increased tourist revenues, the lions would be history before you could blink. For me personally, as an artist, to be able to hear lions roar outside my bedroom at night, and know that I might be drawing them at dawn the next morning lit a fire of inspiration that has seen this book through to its conclusion. But sharing time and space with the people who made these experiences possible was humbling, and I saw at first hand, just how much daily graft goes into keeping these magnificent animals from disappearing from the planet. They are heroes.

The design of Lion is stunning, you let the artwork shine, how did you and Unicorn Publishing work together to create this look?

Many years ago now, I bought (at considerable expense!) a book called Toros y Toreros which was made by Picasso in the late 1950s. It is still one of my favourite possessions, and it was a huge inspiration to me in wanting to make books from my experiences with different wild animals. I bought it when the influence of photoshop and flourishing of graphic design options had made complex design and printing much easier, and it seemed to me that it was the antithesis of all the visual trickery that book design was using. What Picasso did was to make a book on beautiful matt paper with a minimum of intrusion onto the art work. There are no page numbers, no text (other than an introduction) and the colour of the paper, in most cases, acts as the colour of the original full bleed drawing. In other words, rather than getting a catalogue of photographs of drawings with captions and supporting imagery, it is as if you actually have the original drawings in front of you. This is what I wanted people to have in a book of mine, and in Unicorn, I found a publisher who understood this and was happy to take a punt on this idea. Hopefully the (apparent) simplicity and immediateness of the pages will mean that you don’t waste a second thinking about how the images got there or were put together, and the reality of the months of hard graft and endless rearranging of images will magically disappear letting the artwork speak for itself. In the end I had to do the lion’s share (pun intended) of the design work, but Felicity Price-Smith from Unicorn was an essential sounding board throughout and had a crucial hand in the final edit - as well as the beautiful typography (an area in which I have no skill whatsoever).

Your art feels so vibrantly alive, I love that you’ve included sketches, as well as finished pieces, tell us about sketching in the field and why it was important to include them. Tell us about the differences between your work being displayed in a book, and an exhibition.

Thank you so much for saying that the work feels alive - my subject matter is very much alive, and it is one of my main objectives to create art that has an equivalent energy. I have always tried to work from life as much as I can, and where this is not possible to keep in mind the lessons learned in the field - concentrate on the subject, not on the page and let the lines and marks have autonomy and life of their own, working in parallel with the image rather than illustrating it. Every species of animal has its own issues and lions have been no exception. Perhaps most frustrating was so often waiting in Africa’s famous golden hour in gorgeous evening light while the pride slept on under a bush just out of sight, only to start to move just as the light faded completely. Each sighting and therefore each image, was the product of countless days of patient tracking and waiting, but I wouldn't have missed a single moment.

Sometimes a few lines can be more evocative than a heavily worked canvas, and for myself, can have more value, being the product of a brief wondrous moment of intensity and alchemy. In a gallery setting though these lines on cheap sketchbook paper have limited value, both commercially, and in terms of impact (being relatively small). What is so lovely about working on a book is that everything is evened out, and that little page of scribbles can suddenly carry the same weight as a huge canvas that has taken months to produce. I love that.

.jpg)

You’ve essentially invited people to travel with you, to discover your thoughts and feelings through your art, what is the one thing that you hope people will take away with them?

There is almost nowhere in the world where we are not surrounded by images of lions. Valerie Colin-Russ in her original little book “London Pride” counts 10,000 statues of lions in the capital with ease. I suppose what I would hope people would take away from my book is that the myriad centuries of lion imagery made by humans began with a living creature. The lions in the pages of my book are, or in some sad instances, were, living breathing sentient beings, individual in age, sex, looks and character; mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, involved in a complex network of pride relationships, and intricately connected with the whole web of life around them and just as deserving of a place on this planet as the swarm of human beings that have taken it over. So yes, the lion is a potent symbol of many things that humans value and respect. But the lion is also more than just a symbol from history - it is, thanks to a lot of hard work from conservationists, a magnificent wild reality. My time with lions in the wild has been amongst the most amazing in my life to date. If the collection of lines and brushstrokes on these pages can transmute one iota of the wonder that I felt, then it will have done its job...

Be in with a chance of winning your own copy of this stunning book by entering our competition.

If you enjoyed this, check out more 'Author Talk' and 'Book Chat' posts on our blog.

Comments (0)

Leave A Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.